Don’t remember anything about the Regulators from your U.S. History class? Never took U.S. History? Not to worry. Anne Gavin has you covered with this Outlander history lesson.

Regulators? What? Who? I am sure more than a few Outlander television viewers wondered about the Regulator movement and its significance when it was introduced in Outlander Season 4. Since I have only read partial bits of The Fiery Cross and can’t remember from any of my U.S. history courses anything about the Regulators, it was all news to me.

And, then when my beloved Murtagh took the mantle of leader of the Regulators in his new, revived story arc, I was even more curious about this movement and how it may or may not have fit into the history of colonial America. After Outlander Season 5, episode 2 “Between Two Fires,” I had even more questions. What was this uprising all about in North Carolina and who were the Regulators? How much of what we see in the show is historically accurate? I feel a bit embarrassed that I didn’t know more about this but realized I wasn’t the only one. And, in talking to some of my international friends who love Outlander, they knew very little if anything about the Regulators as well.

So I set out to do a bit of research to help explain to those of us yet unaware of this important, seemingly infrequently spoken about, time in U.S. history. I was not a history major nor am I an academic, so I’ll be brief and try to simplify the major aspects of the Regulator movement. If appropriate, I will also try to tie some of this back to Outlander the TV show’s depiction (thus far) of the series of events that took place between 1766 and 1771 known as the War of Regulation.

The Seeds of Rebellion

It seems as if historians are divided on the true “theme” of the Regulator movement. Was it a class conflict? A regional conflict? An occupational conflict? Turns out it was a little of all three and often intertwined. The Regulator movement started in the Province of Carolina ,which at one point became divided into North and South provinces. Both Carolinas became royal colonies in 1729 serving King George II. In the late 18th century a huge number of immigrants came to North Carolina in search of land to farm and freedom to practice their religion. Many of these early North Carolina settlers came to the Piedmont area in the western part of North Carolina, also known as the “backcountry.” They came from New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Virginia and were primarily of German and Scots-Irish descent. Many English indentured servants also arrived in the colonies around this time. Interestingly, prior to the American Revolution, North Carolina was the fastest-growing British colony in North America.

The land these immigrants sought had been vacated by Native Americans and was fertile ground for farming and agricultural endeavors. For many of these immigrants farming this land was difficult. They were creating something out of nothing and working very hard to do so. The beginnings of the unrest really manifested when the backcountry farmers and planters clashed with the colonial officials in the east. The eastern part of North Carolina was where the elite lawyers, court officials, land speculator and representatives of the English crown resided. The eastern officials looked down on the farmers and planters, and colluded to levy unfair, onerous taxes on the landowners in the west. Little actual currency circulated at this time due to the absence of banks or financial institutions. Any actual coin that was in circulation was controlled by the government and court officials who corruptly plotted to drive up the cost of land and taxes. Farmers were unable to pay with goods or chattel so they would either have to borrow money from officials in the east or go to court to try and settle their debt. However, even there, the sheriffs and court officials illegally drove up court fees, putting the backcountry settlers even deeper into debt. Many chose to leave North Carolina and the farms they had created and tended, rather than be subject to the illegal taxes, high land fees and lack of representation amongst the government’s assemblies.

Those that stayed became increasingly angered by the inequality of the tax system, the corruption and the fraud perpetrated by the King’s representatives. The backcountry farmers adopted the name “Regulators” in 1766 to describe their movement to revolt against the corrupt colonial officials and their unfair practices. The term had been used in 17th century Britain and was meant to describe people who were appointed to ferret out government corruption. Given the term’s origins, the North Carolina Regulators felt this provided them with some legitimacy. Surprisingly, the Regulators were incredibly organized and united in their cause. They organized themselves by “neighborhoods.” Those neighborhoods that played the most prominent role in the War of Regulation were Hillsborough, Orange (now Alamance), Salisbury, Wilmington and Rowan. The Regulator movement was born.

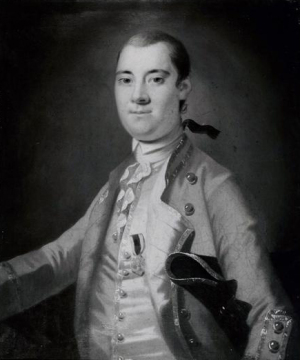

Governor William Tryon

The Regulators and Government Clash

Herman Husband initially led the Regulators. Husband was a farmer and religious leader. Interestingly, Husband denied he was a Regulator and refused to take part in any violence or threats of violence. Indeed, the early acts of the Regulators involved peaceful attempts to petition the government and reform corrupt practices by legal means. Husband published several pamphlets that criticized the government including one verbosely titled, “An Impartial Relation of the First and Causes of the Recent Differences in Public Affairs.”

As part of the effort to correct their lack of representation, Regulators sought to organize politically and elect some of their own to the government’s State Assembly. Husband was twice elected to the North Carolina Assembly but was expelled during his second term, no doubt due to his affiliation with the Regulator movement. On the government side, Edmund Fanning became a focus of much of the Regulators’ ire. Fanning was a good and trusted friend of Governor William Tryon, who had risen from lieutenant governor of the Provinces of North Carolina to governor upon the death of the previous governor in 1765. Fanning presided as clerk of the court in Hillsborough but also colonel of the militia. His corruption was widely known as Fanning sought to enrich himself and his friend, the governor, off the backs of the farmers and planters of the backcountry.

Tryon himself at first could not be bothered with the Regulators. Their pleas to meet with him to discuss the disparity of taxes and the unfair court system fell on deaf ears. Tryon was first and foremost a military officer. He was not a man of the people nor could he be bothered managing the politics of the day. He was disdainful of the backcountry settlers and thought them ignorant and their grievances of little consequence. Many said he underestimated the resolve of the Regulators as he did little to nothing to try and resolve the issues causing the unrest. Tryon refused to meet with the Regulators and ignored the many petitions sent on their behalf, all while accepting the proceeds of the high taxation to fund his palace in New Bern, a particular point of contention with the Regulators.

After numerous failed attempts to legally try and right the wrongs of the corrupt government, the Regulators decided that the only way to create change was by illegal means. It was at this time that James Hunter rose to lead the efforts of the Regulators given Herman Husband’s penchant for non-violence. Hunter took an active role in a raid on Hillsborough where shots were fired, and Edmund Fanning was beaten, and his house burned and torn apart. Thus, began several “closing of the courts” where Regulators took over the bench, kicked out judges and juries and attempted to organize their own “people’s courts.” The Regulators threatened to “hold” all their taxes unless reform was made. The scene was set for a battle that would decisively end the Regulator movement and propel Governor Tryon to further acts of oppression against the settlers of the backcountry.

Battle of Alamance

A Battles Ensues

Tryon began to realize that in attempting to ignore the Regulators he was in fact fanning the fires of insurrection. After the Hillsborough Courthouse protest, the governor worried that Regulators might resort to more violence thereby undermining his rule in the province. In January of 1771, a “Riot Bill” was introduced and passed both houses of the Assembly in New Bern. The law was similar to the English Riot Act of 1714, which declared it illegal for 12 or more people to assemble and to disperse or face punitive action. Tryon’s 1771 Riot Bill took it further and gave the government additional powers to foster an attitude that equated riotous behavior with insurrection. But again, Tryon underestimated the Regulators. As word of the Riot Bill reached the backcountry, it further enraged the Regulators and increased their protests. The act allowed government law enforcers to use force without investigation while declaring rioters outlaws if they remained at large for 60 days. Once outlaws, the act allowed the government to seize and sell the rioters’ property. The final indignity of the act allowed Governor Tryon to raise a militia to execute the law by increasing taxes — which, of course, fell disproportionately on the backcountry settlers.

As mentioned previously, Tryon was a military man whose first instinct was to seek military solutions. In mid-May 1771, when the governor heard that the Regulators had assembled in large numbers at Alamance Creek in western Orange County, he gathered his own militia and headed there to disperse the insurgents. Tryon was outnumbered two to one, as he had only 1,000 men compared to the 2,000 Regulators. But Tryon’s troops were well armed. They had artillery and cannons, and most were officers of rank varying from major-generals to lieutenant colonels to majors of brigade. The Regulators, despite their numbers, were disorganized with no leadership, no officer ranked higher than captain, and little to no ammunition.

Throughout the morning on May 16, 1771, Governor Tryon tried several times to ask the Regulators to lay down their arms. Twice the governor sent dispatches to the Regulators warning that if they refused to surrender, they would be attacked and defeated. By midday the Regulators had again rejected the governor’s terms of surrender. Instead they sent word that they would be willing to exchange some of Tryon’s captured men for seven Regulators that the governor had arrested the day before. The governor agreed to the exchange but when the men did not appear at the designated time, he became suspicious and ordered his militia to march within 30 yards of the Regulator army. Confusion ensued and shots were fired as the Regulators were heard to call out “Fire and be damned!”

The Regulators’ principal military leader, Captain Montgomery, was killed by cannon fire, after which Tryon attempted to force surrender again. But the Regulator troops continued to fight despite rapidly running out of ammunition. Many of the Regulators fled the field of battle as it became apparent that they would be defeated. Quaker and pacifist Herman Husband had long left the field by then. Tryon’s army was better trained and better supplied. Although losses on both sides are disputed, they were relatively small compared to the number fighting. Both Tryon’s militia and the Regulator army counted between 9 and 20 dead with dozens wounded.

The Aftermath

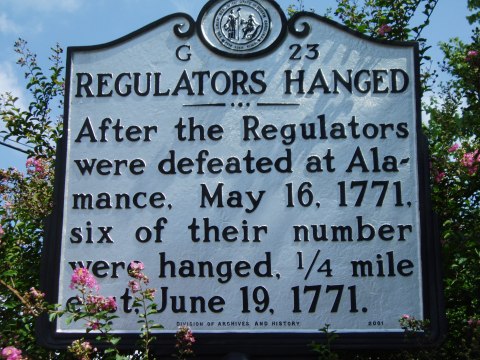

Being a military man, Tryon was not content with having trounced the Regulators soundly at Alamance. He put on trial a few Regulator leaders, including Herman Husband. Several Regulators were pardoned by King George and half a dozen were executed at public hangings. Tryon then took his militia on a punitive march through the Piedmont, destroying farms, taking food and goods and forcing Regulators to sign oaths of allegiance to the British Crown. Tryon did all this just before being re-assigned to become governor of New York. He left for New York just a little over a month after the Battle at Alamance, satisfied he had put down the rebellious Regulators.

Tryon’s successor in the North Carolina Province was Josiah Martin. While also a British officer, Martin was known as more of a conciliator. While initially seeing the Regulators as unruly mobs of malcontents, he later came to understand their plight and was sympathetic. Martin was able to diffuse the situation with the Regulators somewhat with some short-term changes. But structurally nothing really changed with either the unfair taxation or land speculators and their extortion of the backcountry. But, Martin recognized that the Regulators’ complaints were more to do with the inequality of life in the province and the burdens placed on them by high taxes, and less to do with animus towards the crown. In fact, many of the settlers were loyal to King George. Martin cultivated this loyalty and worked closely with Highland Scots immigrants to try to help put down growing unrest that would later become the American Revolution.

Outlander-Online

And so, Outlander…

Murtagh’s insertion in the story makes some sense given the fact that many Scots-Irish immigrants and others were residing in North Carolina at the time of the story. However, Murtagh’s clear loathing of the Redcoats and the governor, doesn’t follow much with the true story. Outlander plays up the hatred of the Redcoats and the English as a recurring theme that tracks throughout the books and the television series. Most historians agree that the backcountry settlers were loyal to the crown but took issue with the unfair way they were being treated by the elite class of government officials in the east of the province. They hated Edmund Fanning because he embodied the corrupt practices they despised and was center to most of the graft perpetrated by the courts in Hillsborough. And, while the Regulators of history did use violence on several occasions, those occasions were very few. Most Regulators preferred non-violent means to obtaining the changes they sought and spent the majority of the time between 1766 and 1771 trying to use legal means to accomplish their goals. Some minor beatings and destruction of property seemed the extent of the Regulators’ tendencies towards violence. So, it would appear that Outlander the TV series took some liberties portraying the Regulators’ tar and feathering in Episode 5.02 as a way to brutalize the colonial officials and court officials. And, as far as the Battle of Alamance, it would appear they knew they were unprepared to fight and gathered themselves that morning of May 16th in such numbers as a show of force only, hoping Governor Tryon would be forced to retreat seeing he was outnumbered two to one. We have yet to see how Outlander the TV series will portray the Battle of Alamance. I look forward to seeing that this season.

In the television series, we see Jamie Fraser trying to fulfill the oath of loyalty he made to the English Crown when he accepted the parcel of land from the governor. Yet, Jamie’s sympathies, as always, lie with the Scots immigrants who are being treated poorly by the colonial officials. Real history shows us that Governor Josiah Martin did try to forge a relationship with many of the immigrant groups in the province, including notably Highlander Scots. I don’t think Jamie’s dilemma is probably too big a stretch, at least thus far in the series.

One question that gets asked a lot by people who know and have studied the War of Regulation in North Carolina is should it be considered a pre-cursor to the American Revolution? It can be argued that yes, it was, as both conflicts were premised on the notion of “no taxation without representation.” However, one distinction is that Regulators didn’t necessarily want to change the government’s form. In fact, several ran and were elected to the North Carolina state assembly. What they did want, though, is to change the political processes that affected them disproportionately. If that had been accomplished, the Regulators would likely have happily gone on to live peacefully with the colonial officials. However, the structural changes the Regulators wanted never happened, so their populist uprising was, in some ways, a precursor to the movement that would thrust America’s 13 Colonies into the great American War of Independence.

If you are interested in learning even more about North Carolina’s War of Regulation check out Mary and Blake Larsen’s Outlander Cast Podcast & Blog interview with Dr. Marjoleine Kars, professor of history at The University of Maryland Baltimore County. Dr. Kars is the author of Breaking Loose Together: The Regulator Rebellion in Pre-Revolutionary North Caroline, which can be found on Amazon.

Did you know anything about the Regulator Rebellion in North Carolina before reading or watching Outlander?

Anne Gavin is a senior writer at Outlander Cast and frequent traveler to Scotland. Anne also writes a series of travel blogs called “The Scotland Diaries.” Her 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019 travel series can be found at Outlander Cast by searching “Scotland Diaries.” Follow Anne on Instagram here or at Outlander Cast’s Instagram here, where many of Anne’s photos of Scotland are often featured.

12 Comments

Leave your reply.